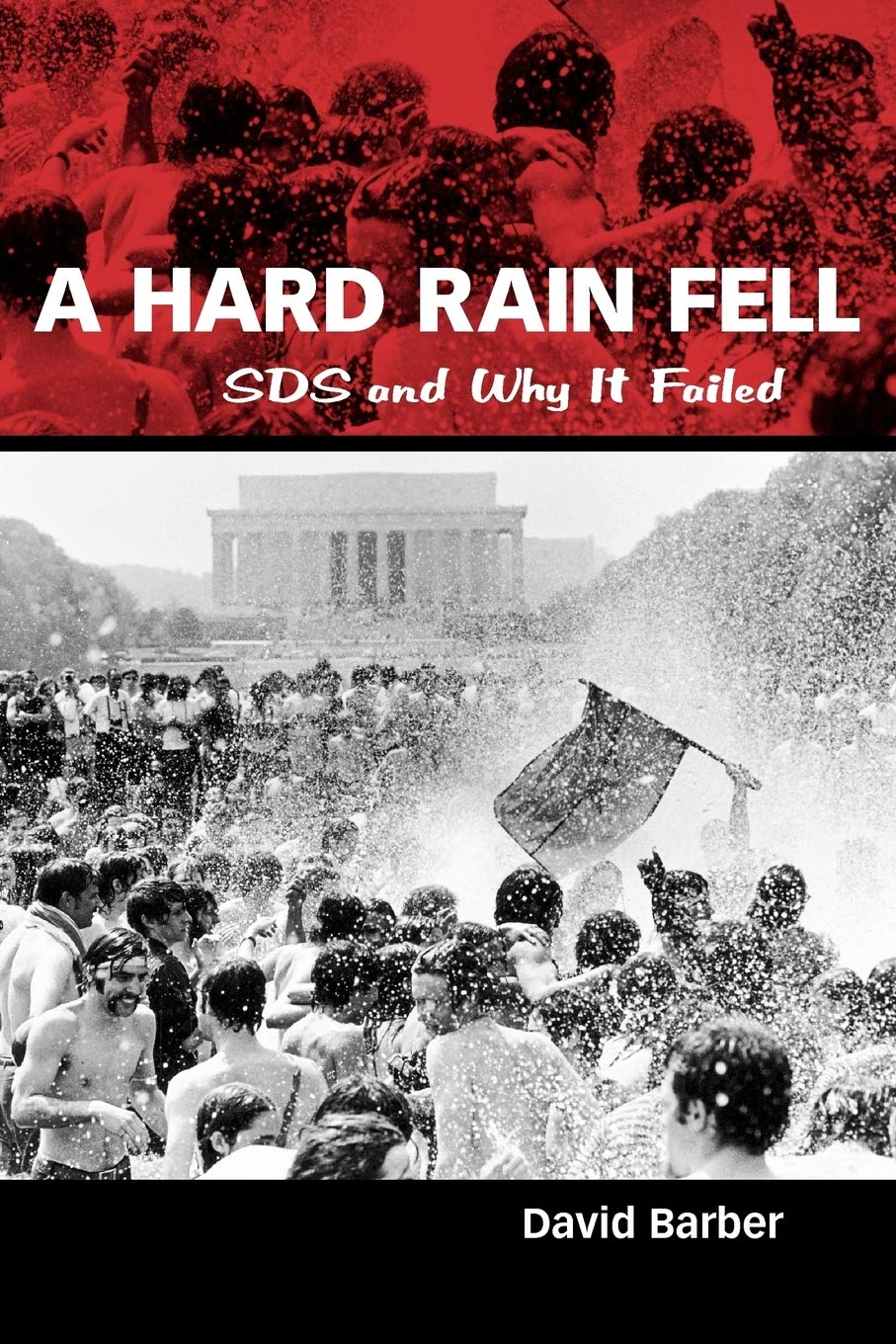

subcutaneous quoted A Hard Rain Fell by David Barber

Dan Berger, Outlaws of America: The Weather Underground and the Politics of Solidarity (Oakland, Calif.: AK Press, 2006), takes its place as the most enthusiastic champion of the New Left and Weatherman specifically. Berger, for example, generally touts a line articulated by the former Weatherman Robert Roth: “Weather’s early politics . . . ‘represented an insistence on up-front support for Black liberation as a centerpiece for any political movement among white people.’ ” (102). That Weatherman indeed articulated such politics cannot be questioned. That in its practice Weatherman also disparaged the two leading black nationalist groups of the day, SNCC and the Black Panthers, ignored their organizational advice and criticisms, and promoted a version of black leadership that did not exist in the social life of black people at the time, this, too, cannot be denied. But Berger avoids a deep analysis of this conflict. In varying degrees, Jeremy Varon, Bringing the War Home: The Weather Underground, the Red Army Faction, and Revolutionary Violence in the Sixties and Seventies (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), and Ron Jacobs, The Way the Wind Blew: A History of the Weather Underground (New York: Verso Press, 1997), both weight their accounts of Weatherman on the side of what the organization was saying about itself, rather than what it actually did, relative to the black and Third World movements of the day. Max Elbaum, Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals Turn to Lenin, Mao and Che (New York: Verso Press, 2002), follows the same methodology in tracing the history of Weatherman’s SDS rival faction, RYM II.

Introduction, endnote 20.